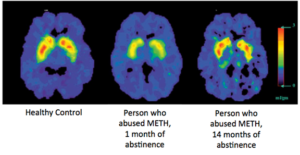

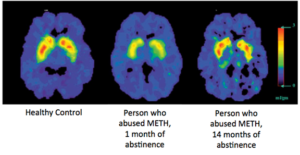

Substance use decreases brain function and changes behavior in ways that those with Substance Use Disorder (SUD) find it increasingly difficult to control. With abstinence or Medically Assisted Treatment (MAT) brain recovery is possible. How the brain recovers from addiction is an exciting and emerging area of research. There is evidence that the brain does recover. The image below shows the healthy brain on the left, and the brain of a patient who misused methamphetamine in the center and the right. In the center, after one month of abstinence, the brain looks quite different than the healthy brain; however, after 14 months of abstinence, the dopamine transporter levels (DAT) in the reward region of the brain (an indicator of dopamine system function) return to nearly normal (Volkow et al., 2001).

There is limited research on the brains recovery from alcohol and marijuana use. However, recent studies have shown that some recovery does take place. For example, one study found that adolescents that became abstinent from alcohol had significant recovery with respect to behavioral disinhibition and negative emotionality (Hicks et al., 2012). Lisdahl and colleagues posit that this could mean that some recovery is occurring in the prefrontal cortex after a period of abstinence. Furthermore, other research has found that number of days abstinent from alcohol was associated with improved executive functioning, larger cerebellar volumes and short-term memory.

While promising, this field of research is in its infancy and there have been conflicting results that instead show minimal to no recovery from cognitive deficits. This is especially true for studies evaluating the brains recovery from marijuana use, specifically IQ. On the other hand, some studies have shown that former marijuana users demonstrate increased activation in parts of the brain associated with executive control and attention. Whether this is associated with the compensatory response or brain recovery has yet to be determined.

What is clear is that alcohol and marijuana do have neurotoxic effects and, to some degree, this damage can be reversed. There is minimal evidence on how we can improve brain recovery from substance use, but emerging literature suggests that exercise as an intervention may improve brain recovery. Physical activity has been shown to improve brain health and neuroplasticity. In previous studies of adults, physical activity has improved executive control, cerebral blood flow and white matter integrity. While none of these interventions have been done in adolescent alcohol or marijuana users, this approach is promising and should be investigated further.